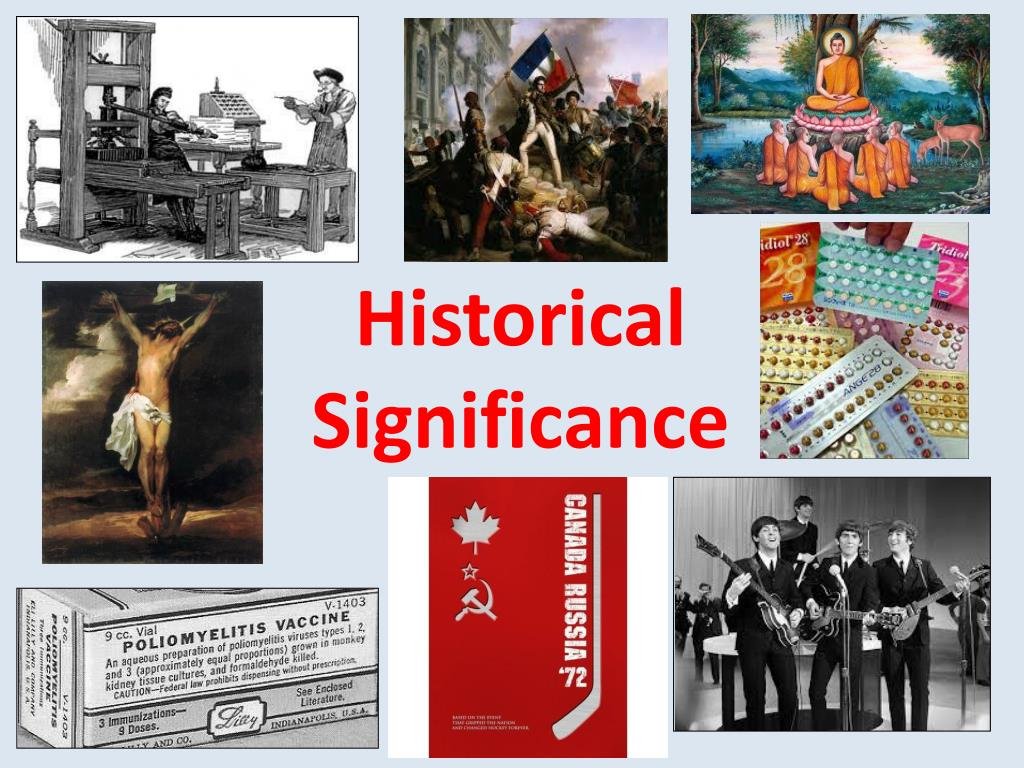

What makes one historical event a foundational pillar of our understanding, while another fades into obscurity? It’s not simply about recording what happened; it's about discerning historical significance. This isn't some dusty academic concept, but a vibrant, ever-evolving lens through which we interpret the colossal tapestry of human experience, evaluating how past events, people, and developments truly shaped our world, influencing the present and casting shadows on the future.

We’re not just chronicling dates and names; we're weighing impact, tracing lineage, and uncovering meaning. The truth is, historical significance isn't a fixed property carved in stone. It's a dynamic, even contentious, quality that shifts with perspective, new evidence, and the values of each generation asking questions about the past.

At a Glance: Understanding Historical Significance

- It's an Evaluation, Not a Fact: Significance is a judgment call, not an inherent quality of an event.

- Dynamic and Fluid: What's significant changes over time and across different cultural perspectives.

- Shaping Our Understanding: It helps us grasp how societies functioned, what drove change, and why things are the way they are today.

- A "Meta-Concept": It's how historians organize knowledge, frame questions, and build coherent narratives.

- More Than Just "Important": It's about why something matters, for whom, and how it connects to broader trends.

- Crucial for Critical Thinking: Understanding significance is fundamental to democratic education and navigating complex public life.

Beyond Dates and Names: What is Historical Significance, Really?

Imagine a vast ocean of past events. Every wave, every ripple, is an occurrence. But only a few, those that leave lasting imprints on the shore, truly register as historically significant. This distinction is crucial because history isn't just a record; it's an interpretation. When we talk about historical significance, we're engaging in a reasoned, evaluative judgment about why something happened, and crucially, why it matters.

This concept acts as a kind of "second-order knowledge" or a meta-concept, allowing us to organize the dizzying array of historical facts into meaningful frameworks. It guides historians in selecting which events to remember, which stories to tell, and which inquiries to pursue. Without it, history would be an overwhelming, undifferentiated list of occurrences. Instead, it becomes a powerful narrative that illuminates cause and effect, patterns of change, and the enduring human condition.

But here’s the critical twist: significance isn't intrinsic. It's not like the weight or color of an object. Instead, it's a contingent quality, entirely dependent on the perspective from which it's viewed. An event considered pivotal by one society or generation might be a footnote for another. This flexibility reflects "a flexible relationship between us and the past," constantly inviting re-evaluation and fresh insights.

Sometimes, the discussion of significance also brings up its quiet counterpart: historical silence. This refers to the events, groups, or contributions that have been systematically excluded or downplayed in historical records. By asking why certain things are deemed significant, we are implicitly asking why others are not, revealing biases, power structures, and the deliberate choices that shape our collective memory.

Why Does It Matter? The Enduring Power of the Past

Understanding historical significance isn't just an academic exercise for scholars cloistered in archives. It profoundly shapes how we understand the world around us, how we make decisions, and even how we envision our future. It’s the difference between memorizing facts and truly grasping their meaning.

First and foremost, it helps us understand past societies. By identifying what was significant to people in a particular era, we gain insight into their values, priorities, and struggles. We learn what drove their innovations, fueled their conflicts, and defined their daily lives. For instance, the significance of a famine isn't just the death toll, but how it reshaped economic systems, triggered migrations, or spurred social reforms.

Secondly, historical significance illuminates how past events influence future events. History doesn’t just happen and then stop; it creates a cascade of consequences. The echoes of past decisions, conflicts, and achievements reverberate through time, shaping geopolitical landscapes, cultural identities, and technological trajectories. Recognizing this causal chain allows us to appreciate the long-term impact of seemingly isolated incidents.

Perhaps most subtly, significance helps us understand how history reflects contemporary values. The questions we ask of the past often reveal our present concerns. For example, a society grappling with issues of social justice might re-examine historical figures or movements through the lens of civil rights, uncovering previously overlooked struggles or contributions. This isn't about rewriting history to fit modern sensibilities, but about discovering new relevance and understanding from historical data, which can sometimes provide a unique perspective, much like how examining the history of 34th Street can reveal layers of urban development and cultural shifts.

Moreover, in an age of information overload, historical significance becomes paramount for organizing historical knowledge and framing areas of inquiry. It’s the compass that guides students and citizens alike to build substantive understanding, helping them discern between vital information and mere trivia. It’s why certain events make it into textbooks while countless others do not – not because the others didn't happen, but because their perceived impact on the larger narrative is different.

This interpretative aspect makes history writing distinct from a mere record of events. A chronicle lists what occurred; a history explains why it matters. This is why historical significance is considered "a fundamental corner-stone of a liberal and democratic education" across numerous national and international curriculums. It equips us to critically assess narratives, challenge assumptions, and engage thoughtfully with public life.

The Historiographer's Lens: How Do We Determine Significance?

If historical significance isn't fixed, how do historians, educators, and even the general public make these crucial judgments? It's not a simple checklist, but rather a process of reasoned, evaluative judgment, guided by a set of disciplinary lenses. These lenses help us to move beyond a gut feeling of "importance" to a structured argument about why something deserves our attention.

The Historical Thinking Project, a leading initiative in history education, suggests that significance is acquired when "we, the historians, can link it to larger trends and stories that reveal something important for us today." This highlights the connection between the past and the present, and the active role of the interpreter.

Let's break down some of the criteria, or "lenses," commonly used to assess significance:

- Contemporary Significance: How important was the event to the people living through it at the time? Did it alter their lives, their beliefs, or their immediate future?

- Causal Significance: Did the event cause widespread change or have long-lasting consequences? Did it trigger a chain reaction that altered the course of future events?

- Pattern Significance: Does the event exemplify or illustrate a larger trend or a recurring pattern in history? Does it help us understand broader forces at play?

- Symbolic Significance: Did the event come to represent something larger than itself? Did it become a symbol of an idea, a movement, a triumph, or a tragedy?

- Revelatory Significance: Does the event reveal something profound about human nature, societal structures, or the values of a particular era that was not previously clear?

- Present Significance: How relevant is the event to our understanding of the world today? Does it help us make sense of current issues, challenges, or identities?

These criteria are not mutually exclusive; an event can (and often does) exhibit multiple forms of significance. They function as tools for argumentation, enabling us to build a case for an event's lasting impact rather than simply stating it as a given.

Case Study: The Suez Crisis of 1956—A Masterclass in Shifting Significance

To truly grasp how historical significance works, let's turn to a potent example: the Suez Crisis of 1956. On the surface, it was a geopolitical standoff involving Egypt, Britain, France, Israel, and, critically, the United States and the Soviet Union. But its historical significance far transcends the immediate events of a short conflict.

1. Decline of Colonial Powers and Rise of Superpowers (Causal & Pattern Significance):

The crisis definitively underscored the precipitous decline of British and French colonial influence on the global stage. Their unilateral action, bypassed by their American ally and condemned by the international community, revealed their diminished power. Simultaneously, it marked a pivotal shift towards American and Soviet dominance in global politics, ushering in a new era of Cold War rivalry for influence in crucial regions like the Middle East.

2. Reshaping Middle Eastern Geopolitics and Arab Nationalism (Causal & Revelatory Significance):

The Suez Crisis dramatically altered Middle Eastern geopolitics. Egyptian leader Gamal Abdel Nasser, despite military setbacks, emerged a hero in the Arab world for standing up to former colonial masters. The crisis fostered a surge in Arab nationalism, demonstrating the power of newly independent states to challenge established global orders. It revealed the potent force of anti-colonial sentiment and the growing desire for self-determination.

3. The United Nations and International Law (Symbolic & Pattern Significance):

The crisis showcased the United Nations' evolving role as a mediator in Cold War conflicts, especially through the establishment of the first large-scale UN peacekeeping force. It symbolized a growing, albeit imperfect, commitment to international law and collective security, highlighting the need for global cooperation to prevent larger conflagrations.

4. Enduring Strategic Importance (Present & Pattern Significance):

Beyond the immediate political fallout, the Suez Crisis highlighted the enduring strategic importance of access to vital trade routes and resources, specifically the Suez Canal and Middle Eastern oil. This lesson has continued to influence modern maritime security policies, energy transportation strategies, and global trade dynamics, proving its ongoing relevance today.

Each of these facets contributes to the Suez Crisis's layered significance. What was initially seen by some as an attempt to reassert colonial power became, through the lens of history, a powerful symbol of decolonization, the rise of a multipolar world, and the nascent influence of international institutions. Its significance is not a singular, simple fact, but a complex interplay of consequences, symbols, and revelations that continue to shape our understanding of the 20th century and beyond.

Unpacking the Criteria: A Closer Look at Evaluating the Past

To truly engage with historical significance, it helps to understand these disciplinary lenses in more detail. They offer a framework for asking specific questions about an event, person, or development, moving beyond a general sense of "importance."

Causal Significance: The Ripple Effect

This is arguably the most straightforward criterion. Did the event directly cause significant changes? Did it set off a chain reaction? Think of it like dropping a pebble into a pond – the causal significance is the ripples that spread out, some reaching distant shores.

- Example: The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand (1914) had immense causal significance because it directly triggered a series of alliances and declarations of war, leading to World War I. Its immediate impact was undeniable and far-reaching.

Pattern Significance: Spotting the Trends

Some events are significant not just for what they caused, but for what they represent within a broader historical context. Does the event exemplify a larger trend, a recurring human behavior, or a specific stage in a historical process?

- Example: The Black Death (mid-14th century) wasn't just a devastating pandemic (causal significance); it also serves as a potent example of how demographic shocks can fundamentally restructure societies, economies, and religious beliefs, illustrating a pattern seen in other periods of widespread disease or catastrophe.

Symbolic Significance: More Than Meets the Eye

Often, an event or person transcends its immediate context to become a powerful symbol. It might represent an idea, a struggle, a turning point, or a collective memory. The symbolic meaning can sometimes be more enduring than the direct causal impact.

- Example: The fall of the Berlin Wall (1989) had causal significance in ending the Cold War, but its symbolic significance was perhaps even greater. It became the ultimate representation of the collapse of communism, the reunification of Germany, and the triumph of freedom over oppression, resonating far beyond its physical location.

Revelatory Significance: Unveiling Hidden Truths

This criterion focuses on what an event reveals about the past that might not have been evident before. Does it shed light on underlying societal tensions, cultural values, power dynamics, or the true nature of institutions? It often uncovers previously unseen aspects of human experience.

- Example: The Watergate scandal (1970s) was causally significant for leading to a presidential resignation and legislative reforms. But its revelatory significance was profound: it exposed the abuse of executive power, the fragility of public trust, and the deep-seated corruption that could exist at the highest levels of government, fundamentally altering public perception of political authority.

Present Significance: Echoes in Our Time

How does a past event speak to us today? Does it help us understand our current challenges, identities, or global position? This lens acknowledges that our interpretation of the past is always, to some extent, colored by the concerns of the present.

- Example: The drafting of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948), while causally significant for establishing international legal norms, holds immense present significance as nations continue to grapple with human rights abuses, refugee crises, and the ongoing struggle for universal dignity. It serves as a foundational text for contemporary debates.

Contemporary Significance: What They Felt Then

Finally, it's vital to consider how an event was perceived and experienced by the people living through it. What was its perceived importance at the time? This helps us avoid anachronism and understand the immediate emotional, political, and social impact.

- Example: The launch of Sputnik (1957) was a shockwave. For contemporary Americans, its significance was immediate and terrifying: a challenge to technological supremacy and a direct threat to national security, igniting the Space Race and a wave of educational reforms. Its contemporary significance was felt acutely.

By applying these various lenses, we can construct a robust and nuanced argument for an event’s historical significance, moving beyond simplistic pronouncements to a deeper, more analytical understanding.

Navigating the Nuances: Common Pitfalls and Misconceptions

Engaging with historical significance requires careful thought to avoid common traps that can distort our understanding of the past. It’s easy to project our own views, but a truly insightful approach demands intellectual humility and a commitment to critical thinking.

Misconception 1: Significance is Objective and Universal

One of the biggest errors is believing that an event's significance is a fixed, objective truth that everyone everywhere should agree upon. This ignores the subjective nature of interpretation. What is profoundly significant to one culture or community, due to shared heritage or direct impact, might be less so to another.

- Clarification: Significance is always constructed. It's negotiated and debated, reflecting the values, perspectives, and historical contexts of those doing the evaluating. It means acknowledging that there can be multiple, valid interpretations of an event's importance.

Misconception 2: Significance Equals "Good" or "Bad"

Often, we conflate an event's importance with its moral value. While many significant events have profound ethical dimensions, significance itself is about impact and consequence, not inherent virtue or vice. Both triumphs and catastrophes can be historically significant.

- Clarification: The Holocaust is historically significant not because it was "good," but because of its unparalleled human cost, its revealing nature about human cruelty and state power, and its lasting impact on international law and memory. Its significance lies in its profound consequences and revelations, regardless of its moral abhorrence.

Misconception 3: Presentism – Judging the Past by Today’s Standards

This is a particularly seductive pitfall. Presentism occurs when we judge past actions, beliefs, or figures solely through the moral and cultural lens of the present, without adequately understanding their own historical context. While reflecting on the past through contemporary values is part of present significance, it's crucial to distinguish this from anachronistic condemnation.

- Clarification: To understand the significance of, say, the treatment of women in a 17th-century society, we must first understand the social norms, religious beliefs, and legal frameworks of that era. Only then can we analyze how those practices diverge from our present values and what that reveals about historical change. It’s about understanding, not just judging.

Misconception 4: Only "Great Men" (or Women) Make History

This perspective often overemphasizes the role of extraordinary individuals while downplaying the broader social, economic, and cultural forces at play. While charismatic leaders or brilliant innovators certainly have their impact, history is also shaped by collective action, technological shifts, environmental factors, and the daily lives of ordinary people.

- Clarification: The Industrial Revolution was profoundly significant, not just because of figures like James Watt, but because of a confluence of technological advancements, available resources, demographic shifts, and evolving economic systems. Attributing it solely to a few inventors misses the complex interplay of factors.

Navigating these nuances allows for a richer, more accurate understanding of history, fostering genuine intellectual curiosity rather than simplistic judgments. It trains us to be discerning consumers of historical narratives, whether they appear in textbooks, documentaries, or political discourse.

Your Role in the Story: Engaging with Historical Significance Today

Understanding historical significance isn't just for professional historians; it's a vital skill for every citizen. In an era where information is abundant but often unchecked, the ability to critically evaluate historical narratives is more important than ever. You have a role in interpreting, questioning, and even shaping the ongoing conversation about the past.

Here’s how you can engage with historical significance in your daily life:

- Question the Narrative: When you encounter a historical claim or story, ask yourself: Why is this story being told now? Whose perspective is it from? What aspects might be left out? Every historical account is a selection, and understanding the criteria behind that selection is key.

- Seek Multiple Perspectives: Don't settle for a single account. Explore different interpretations of the same event from various sources, cultures, and time periods. This helps you build a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of its significance. An event's impact often looks very different depending on whether you were on the winning or losing side, or an observer from afar.

- Connect Past to Present: Actively look for the "present significance" of historical events. How do past decisions or movements relate to contemporary issues like climate change, social inequality, or geopolitical tensions? This practice makes history tangible and relevant to your world.

- Recognize the Construction of Memory: Understand that historical significance is often tied to collective memory and identity. Monuments, holidays, and national narratives are all ways societies remember and give meaning to the past. Be aware that these can also be contested and change over time.

- Be Aware of "Historical Silence": Think about what isn't being talked about. Whose voices or experiences might be missing from the dominant historical narratives? This awareness can lead to a deeper, more inclusive understanding of history.

This critical engagement with the past, guided by an understanding of historical significance, is a cornerstone of informed citizenship. It helps you dissect political rhetoric that selectively uses history, appreciate the depth of cultural traditions, and contribute thoughtfully to societal debates.

Making Sense of Yesterday for a Better Tomorrow

Ultimately, the concept of historical significance reminds us that history is not a static collection of facts, but a living, breathing conversation between the past and the present. It’s a recognition that every generation, equipped with new questions, new evidence, and new perspectives, has the power to re-evaluate and reinterpret what truly matters from the annals of time.

This dynamic process isn't about relativism or dismantling truth. Instead, it’s about enriching our understanding, revealing the layers of complexity that define human experience, and helping us learn from the triumphs and tragedies of those who came before. By honing our ability to identify, analyze, and debate historical significance, we don't just become better students of history; we become more thoughtful, critical, and engaged participants in the unfolding story of our world.

So, the next time you encounter a historical event, don't just ask what happened, or when. Challenge yourself to ask: Why does this matter? For whom did it matter? What does it reveal? And how does it connect to the larger human journey? In answering these questions, you unlock the true, lasting power of the past.